|

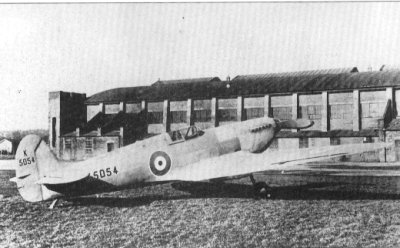

The first Spitfire flown from Eastleigh in front

of a hanger built for the USNAFin 1918

The story of Reginald Joseph Mitchell is so

inspiring — and such a sad one, too — that its appeal to that great romantic star Leslie Howard was understandable. Actor-director Howard saw

his 1942 film The First of the Few as a wartime propaganda vehicle and the role of Mitchell as

another opportunity to play one of those absent-minded dreamers that were his

specialty.

According to Dr Gordon Mitchell, editor and part-author of R. J. Mitchell (Nelson and

Saunders, 1986), his father, though blond and blue-eyed like Howard, was temperamentally the

complete opposite: '''forceful, strong, quick-tempered and very much awake all the time." Ironically,

neither Mitchell, whose Spitfire helped to win the Battle of Britain, nor Howard, who played him,

lived to sec the Nazis defeated — R. J. died of cancer in 1937 at the tragically early age of 42 and

Howard was never heard of again when his plane went missing in 1943.

Reg Mitchell was born in 1895 at Stoke-on-Trent (where there's a Spitfire museum as well as a

school named after him) and began life as a locomotive engineering apprentice. But he was

always mad about aircraft and in 1917 became personal assistant to Hubert Scott-Paine at the

Supermarine Aviation works in Woolston, Southampton. Two years later he was chief designer.

|

R.J.Mitchell,

designer of the Spitfire,

at Eastleigh with 'Mutt'Summers, test pilot,

H.R.Payne Assistant, S. Hall, Air Ministry Officer,

and J.Quill, test pilot |

Mitchell's boss was obsessed with winning the Schneider Trophy, an international award

presented to the nation having the fastest seaplane over a measured course, and in 1922 Supermarine

successfully challenged the Italians with Sea Lion II, Mitchells redesign of the firm's 1919 entry.

Southampton's citizenry turned out in Cup Final style to celebrate and the old Floating Bridge was

decked with flags as it carried the trophy over the water to the victor factory.

The 1923 competition saw the Americans beating Supermarine's entry Sea Lion III. Though

the result was a setback for Mitchell, by the following year he had signed a ten-year contract as the

company's chief designer and engineer, heralding a period which was to see many triumphs. In the

20 years of his life with Supermarine, the man his test pilots called "Mitch" designed a grand total of

24 aircraft — flying boats, amphibians, light planes and racing seaplanes, the Spitfire and a

bomber he was working on when he died.

Mitchell's Schneider ambitions with his streamlined monoplane the S.4 were dashed when

the seaplane met with an accident during its trials, but in the 1927 contest — Britain dropped out in

1926 — he proved triumphant by regaining the trophy for Britain with the S.5 at Venice. Back

home there were more celebrations, though characteristically the modest Mitchell disclaimed

an individual victory: he always regarded himself as the leader of a team.

In 1929 Supermarine, which had been taken over by Vickers, entered their S.6 in the contest

(now held every other year). September 7 was a beautiful day for the race — cars jammed the roads

and the Solent was alive with boats of all types for what turned out be be another British win. Since

the S.6 had a Rolls Royce engine it was unsurprising that the firm should provide R. J. Mitchell

with one of their cars in appreciation of his genius. By now he was looking up in the world, with a

nice house, built to his own design, in Russell Place at Highfield.

The Schneider Trophy races undoubtedly cheered people up in a time of economic gloom,

but in 1931 the Labour Government was reluctant to fork out for his kind of entertainment.

Luckily an anti-socialist millionairess. Lady Houston, was prepared to put up .£100,000 and thus

embarrass poor old Ramsay MacDonald. On this occasion, with the S.6B, Britain won the Trophy

outright — which meant for all time.

These were the Depression years, but Supermarine, with its Schneider successes behind it and

a continuing production of marine aircraft, increased the Woolston factory staff at a time

when other firms were decreasing theirs. Mitchell was working on what would be his greatest

creation, the Spitfire, when something appalling happened: the designer was taken seriously ill and had

a major operation for cancer. This was in the summer of 1933, yet "'Milch'" carried on valiantly —

less than a year after his operation he obtained his pilot's licence.

Early in 1936 the prototype Spitfire was ready to be tested. R. J.'s chairman Sir Robert McLean

thought up the name, though the designer is said to have described it as "bloody silly'"! The fighter

flew for the first time on March 5, 1936, taking off from Eastleigh Airport. The Echo enthused:

"Even the uninitiated have realised when watch- ing the streamlined monoplane flash across the sky

at five miles a minute (300 mph) that here is a plane out of the ordinary."

The sad irony is that Mitchell, who died the following year, didn''t live to see his creation, the

most famous of all fighter planes, play its vital role in saving his country from Nazi domination.

Almost 23,000 Spitfires and Seafires were built— a remarkable figure.

Mitchells brilliance, not always fully recognised during his lifetime, has been admirably

acknowledged in both his native town and adopted city since his death. A youth centre, a

museum, scholarships, schools and lectures, a road, an office block and a development of flats

have all been named after him.

|