| The CRYPT Mag |

Annie Cruickshank shivered with the cold wind blowing through the platform of Edinburgh station. "AYE! It had been a right stormy day, and the night would fare no better" she thought. Annie was a Domestic servant, working downstairs in a large house in Edinburgh. Once a month she finished on a Sunday Evening and did not restart until the following Tuesday .. She spent this valuable time off travelling to Dundee to visit her younger sister.

Mary was younger by 5 years, she disapproved of Annie working as a Domestic, easy for her to be critical, she had a wealthy husband and a nice home, and money to spare. Not that Annie had always been in service, No! Married young to her wonderful Bob, Life had seemed so different. He had a good steady job that paid well and the future looked bright for them both. AH! but that was 20 years ago thought Annie. Almost to the DAY, since the foreman arrived at her humble home to tell her of the accident that robbed her of her Husband.

Annie was startled out of her memories by the shrill steam whistle of the train. Dead on time thought Annie glancing at her Watch 16.14 pm Sunday 28 December 1879.

A slight smile creased Annieís lips as she boarded the train, obviously some people had not completed their Christmas celebrations, Or perhaps it was a practice for Hogmanay, Several people seemed in high spirits.

At least the carriage shut out the driving rain and freezing wind, and the train pulled slowly out of the Station, it would take just over two hours to reach Dundee, so Annie settled down with her book.

Almost two hours later the train arrived at the tiny station of St. Fort, which stands exactly at the south end of the Tay Bridge. The driver and Station attendant exchanged a few words and the section token, the station attendant hurried back into the shelter of the station and the train pulled out and onto the Tay Rail Bridge.

Although Annie had been deeply engrossed in her book, the definite change of the noise of the Locomotive wheels alerted her that they had started the bridge crossing. Not long now she thought and started packing up her goods, ready to disembark on arrival at Dundee station.

Suddenly, without warning the carriage lurched violently to the right. The passengers were thrown across the carriage and up against the right hand side wall. Annie, who had been standing, smashed her head against the bulkhead and she fell to the floor bleeding and dazed.

She could hear the screams, they seemed to be away in the distance, suddenly she was thrown over and over again. The carriage was in darkness, the screaming the grinding, crashing, sound of tortured metal and splintering wood seemed to surround her. Finally a Crash or was it a splash! ... COLD ...very cold water swirled around her. COLD murky water in her mouth in her nose, couldnít move ... trapped ... the blackness over took her, and finally there was peace.

OK! so the above is a little bit of Fiction with some facts thrown in, truth is no one knows really what happened on board the Train that evening, and as all passingers and crew died in the accident, there was no one left to explain the terror felt as the carriages fell from the bridge and into the freezing winter waters of the Tay.

What we do know is that this tragic accident did happen, How or why it occurred has been debated and argued over for almost the last 125 years. In this article we will look at the building of the bridge, the accident and perhaps give some clues to what may have happened on the fateful night.

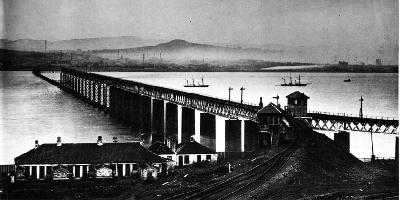

The first Tay Bridge took six years to build, using 10 million bricks, two million rivets, 87,000 cubic feet of timber and 15,000 casks of cement.

Six hundred men were employed throughout the construction, 20 of whom lost their lives.

The final cost of the bridge construction was just over £300,000 .. a princely sum at the time.

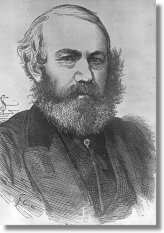

Thomas Bouch. Bouch was responsible for the design, construction and maintenance of the bridge. Most of his bridges were lattice girders supported on slender cast iron columns braced with wrought iron struts and ties.

The bridge was nearly two miles long, consisting of 85 spans and at the time was the longest bridge in the world. The spans carried a single rail track; 72 of these spans were supported on deck spans, the remaining 13 navigation spans were through girders. These "high girders", as they were known, were 27 ft high with an 88 ft clearance above the high water mark. It was these spans which fell.

Bridge time scale:

Bouch appointed to the Edinburgh and Northern Railway 1849

Tay Bridge proposal put to North British Railway 1854

Act passed to approve Tay Bridge July 1870

Contract signed to build a bridge across the Tay October 1872

Survey of estuary December 1872

Start of site work January 1873

Wormit foundry at south end of bridge built February 1873

Hopkins, Gilkes & Co take over construction contract July 1874

Accident in caisson on pier 54; 6 die August 1875

Fall of main girder in storm February 1877

Bridge finished and first train passes over September 1877

Testing of the bridge by Major-General Hutchinson February 1878

First passenger train passes over completed bridge May 1878

The bridge attracted the attention of many at home and abroad, including General Ulysses Grant, who visited to view the construction in 1877.

Although Queen Victoria was unable to open the bridge, she did cross it in the summer of 1879, shortly before she knighted Thomas Bouch.

Just after 7pm the signalman at St. Fort exchanged tokens with the engine driver, This "Token" or "Staff" was required to allow the train to progress through the next section of track. The idea being that it would ensure that only one train at a time could be on a certain length of track.

The train then enter the Tay Rail Bridge heading towards Dundee. The staff at St. Fort telegraphed Dundee to comfirn the departure of the Train.

At around 7.30pm the staff at Dundee station became concerned over the non arrival of the train and tried to contact St Fort station, but to no avail. Of course now we know that the bridge carrying both the train and the Telegraph wires had blown down.

Staff menbers from Dundee station were dispatched on to the bridge to search for the missing train (Some people had reported seeing a red light on the bridge and thought that the train had perhaps broken down during the crossing.

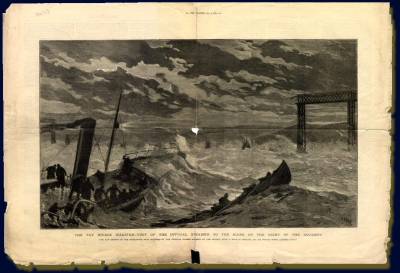

So fierce was the wind that night (force 10 to force 11 Gales) that staff had to crawl along the bridge to avoid being blown off the structure. It was with horror that staff discovered a large section of the bridge and of course the train had collapsed into the waters of the Tay.

Despite the dreadful weather conditions on that night, rescue boats were launched to look for survivors ... there were none!

The days after the disaster were very busy indeed. The high girders that had collapsed and of course the train was blocking the shipping lane of the Tay (The "High Girder" section of the rail bridge was designed to allow shipping to sail under the bridge). The sad task of finding the bodies and personal effects of the dead passingers, was also extremely difficult in the circumstances.

According to ticket sales and including the train crew, it was estimated that 75 people had been on the train when the bridge collapsed, Of course this figure would not have included anyone who may have boarded the train without purchasing a ticket (Something not uncommon on the Railways).

For months after the disaster, bodies were still being washed up along the banks of the river. However only 46 bodies were retrieved, the rest presumably washed out to the open sea, and for months later wreckage from the disaster was washed up sometimes at a distance of 150 miles from the disaster area.

The morning after the disaster, the Post Office sent men to the beach at Carnoustie . There were several bags of mail from the train washed up on the beach...These items were taken to Dundee Head Office and were duly dried and delivered on the second delivery that day...with an apology from the G.P.O. for the lateness of the delivery.

The Board of Trade inquiry into the disaster started in Dundee January 1880.

Board of Trade inquiry in London to hear expert evidence April 1880.

Final report to Parliament in London June 1880

Even by todays standards, the Inquiry into the disaster happened very quickly indeed ... in fact the final report was only 6 months after the accident. Some say the speed of this enquiry was required so other bridges could be checked to prevent further disasters. However another explanation could be offered.The Tay rail bridge was the pride of British engineering, Marvelled at throughout the world. Famous people from around the world visited the bridge and expressed their admiration for such a wonderful feat of engineering. The collapse of the Tay bridge was a major embarrassment not only for the Railways, but for all British engineers and the Government. Perhaps the only way to save face, would be to find a SCAPEGOAT.

There is no evidence to show that there has been any movement or settlement in the foundations of the piers;

The wrought iron was of fair quality;

The cast iron was also fairly good, though sluggish on melting;

The girders were fairly proportioned for the work they had to do;

The iron columns, though sufficient to support the vertical weight of the girders and trains, were owing to the weakness of the cross-bracing and its fastenings, unfit to resist the lateral pressure of the wind;

The imperfections in the work turned out at the Wormit foundry were due in great part to want of proper supervision;

The supervision of the bridge after its completion was unsatisfactory;

If by loosening of the tie bars the columns got out of shape, the mere introduction of packing pieces between the gibs and the cotters would not bring them back to their positions;

Trains were frequently run through the high girder at much higher speeds than at the rate of 25 mph;

The fall of the bridge was probably due to the giving way of the cross-bracing and its fastenings.

The imperfections in the columns might also have contributed to the same result.

This report laid the blame for faulty design, construction and maintenance at Bouchís door. However this finding came as no real surprise. After the completion of the Tay bridge Bouch was hired to design and build the New FORTH rail bridge, indeed he had already laid the foundation stone for this bridge, however after the collapse of the Tay bridge Bouch was removed from office and construction was handed over to Sir William Arrol. Not only was William Arrol given the contract to build the New forth bridge, he was also contracted to design and re-build the tay bridge.

Reputation in tatters Thomas Bouch retired and died at home 30th October 1880, only a few month after the Department of Trade enquiry.

The results of the Board of Enquiry investigation laid blame for the bridge collapse firmly on the design, poor quality of materials and poor maintenence. Thomas Bouch was held responsible in all cases, He was now dead ... CASE CLOSED!

It was indeed Case Closed, despite many people disagreeing with the board findings the case has never re-opened, amazing when you concider that much of the evidence seems to have been ignored by the enquirey. Lets us look at some of the boards findings.

The cast iron was also fairly good, though sluggish on melting;

Strange, I assume they refer to the "Lugs" that tied the cross members to the vertical stantions. Cast Iron .. while a very strong material, can weaken and fracture at low tempetures (1879 was a very cold winter). Also cast iron would not withstand sideways tension, most of the "lugs" on the destroyed bridge section were found to be broken.

The iron columns, though sufficient to support the vertical weight of the girders and trains, were owing to the weakness of the cross-bracing and its fastenings, unfit to resist the lateral pressure of the wind;

If this was the case, Why was two thirds of the bridge still standing? Only the centre section (the High girder section) collapsed. If the iron columns could not support the lateral pressure of the wind, surely the whole bridge would have been affected.

The imperfections in the work turned out at the Wormit foundry were due in great part to want of proper supervision;

When starting to build the bridge, Thomas Bouch was dismayed by the lengh of time it was taking to get the steel. So he built the "Wormit foundry" on the shores of the Tay and made his own steel. The Board of Trade seem to indicate that this steel was inferior quality and not suitable for the construction.

However .. the steel from the original bridge (Both the reclaimed collapsed section and the parts still standing) were re-used by William Arrol in the construction of the NEW tay bridge, the one that is still currently standing and used daily ... 130 years later.

The supervision of the bridge after its completion was unsatisfactory;

This is certainly true, Thomas Bouch WAS responsible for this, However he was by then involved in the plans to construct the Forth Rail Bridge. The bridgemaster appointed to oversee maintenance was totally unqualified, and he Ďrepairedí defects using material bought over-the-counter from a Dundee ironmonger. Most of these repairs were carried out without the knowledge of Thomas Bouch.

Trains were frequently run through the high girder at much higher speeds than at the rate of 25 mph;

Strange that this finding attracted little or no interest. Obviously Thomas Bouch could not be held responsible for this. No .. this was certainly down to the North British Railway company who operated the line. The Tay bridge was built with a speed restriction of 25mph .. but trains often recorded speed of 40/45mph during the crossing. During the 1800`s Railway Companies competed with each other trying to cut journey times and maximum profits. Indeed even with todays high Railway standards trains would not be allowed to cross a bridge in weather conditions with gales of force 10/11. On the night of the disaster rail staff expressed concerns over train using the bridge during the storm, however no one had the authority to canncel the service.

There are two crucial letters in the North British Railway Company's archive that showed that two girders had actually fallen into the river in February of 1877. And this fall is quite well documented, it concerned the two girders spanning piers 28, 29 and 30.

The inquiry was told that two girders had actually fallen into the river in February of 1877, during the bridgeís construction. It was fully published in the press, it wasnít hushed up at all. But what isnít so well known is that the construction company realised that if they were going to get the bridge finished by September of 1877 they just didnít have enough time to make two extra girders over and above what they already had to make anyway. Each girder took about four weeks and required a spring tide for raising. So they left one at the bottom and made a completely new one to replace it, but they repaired the other girder that had fallen in.

The girder needed to be straightened out because when it fell into the river bed it bent due to the fact that the river bed was not flat, but curved as a result of scour. Now when you straighten anything out itís never quite as strong as it ever was before.

Now that girder was riveted to the next 4 girders, so the end of the girder must have been held straight by means of the other girders behind it. But because of the hammering from trains going over it that girder would have reverted to the shape, or as close as it could, that it had on the bottom of the river.

As the girder bent, it would have forced the rails to bend with it, and there were certainly reports that as the trains came along the low girders from Wormit and entered the high girders the engines nodded into the girder. In other words it went slightly downwards and then went slightly eastwards.

Also when divers started recovery of the train carriages, they lifted out, what they thought was the rear Guards Van. However when this was lifted to the surface they actually found that it was two seperate coaches (The last passinger coach and the Guards van) but which had impacted together so hard they appeared as one.

There could be only one explanition for this severe impact. The passinger coach MUST have come to a complete halt and the guards van (Still travelling at high speed) hit into it. ( this impact damage could not have been caused by the coaches colliding while falling or landing on the sea bed, the forces would not have been suffient to fuse the vechicles together in the manner they were discovered).

Although we will never know for sure, The disaster may have been caused by a series of events that ultimately caused the collapse of the Tay bridge.

As the train crossed the bridge it crossed the damaged girder section, causing the train coaches to dip downwards and over to the right hand side. At the same moment a severe gust of wind hit the train broadside from the left. In the 1800`s train coaches were designed with curved roofs, but with uneven bottoms (Flat bottoms with Wheels etc.). This is virtually the same design as an aircraft Wing. The air rushes over the top curved surface at high speed, but the air is much slower underneath .. causing uplift.

Of course railway carriages do not normally get hit with such severe cross winds as most pressure come from the headwind of being pulled forward by the engine.

So if one of the train coaches hit the damaged girder and at the same time a strong cross wind lifted the carriage (ever so slightly) the coach would have become derailed.

It is interesting that a piece of wood recovered from the destroyed bridge seems to show the iron wheel marks embedded deep into it, (Of course this might have happened when the bridge fell over, but could also indicate a derailment).

Now if the last passinger coach was derailed and impacted against the side of the bridge, with the guards van hitting it at high speed, this may have been enough to uncouple the damage girder section, causing a chain reaction (Domino effect) pulling down the remainder of the "high girder" section.

The force of the train colliding with the bridge could easily have snapped the cast iron "lugs" holding the cross braces to the bridge columns, The already weakened bridge would have stood no chance and disaster loomed.

Thomas Bouch will always be remembered as the man who designed and built the Disaster known as the Tay Bridge. Certainly his design was not the greatest in the world, but perhaps, just perhaps it was an unforseen series of events that brought his dream bridge crashing down, and not purely bad workmanship.

| Surname | Forename | Age | Occupation | Address | |

| 1 | Anderson | Joseph | 21 | Compositor | 13, South Ellen Street |

| 2 | Annan | Thomas | 20 | Iron turner | 48, Princes Street |

| 3 | Bain | Archibald | 26 | Farmer | Mains of Balgay |

| 4 | Bain | Jessie | 22 | sister of above | Mains of Balgay |

| 5 | Benyon | William H | n/a | Photographer | Cheltenham |

| 6 | Brown | Lizzie | 14 | Tobacco spinner | 28, Arbroath Road |

| 7 | Cheap | Mrs | 51 | Domestic Servant | 121, High Street, Lochee |

| 8 | Crichton | James | n/a | Ploughman | Mains of Fintry |

| 9 | Cruickshank | Annie | 54 | Domestic Servant | Moray Place, Edinburgh |

| 10 | Culross | Robert | n/a | Carpenter | Newport |

| 11 | Cunningham | David | 21 | Mason | 23, Pitalpin Street, Lochee |

| 12 | Davidson | Thomas | 28 | Farm servant | Linlathen |

| 13 | Easton | Mrs | n/a | Widow | n/a |

| 14 | Fowlis | Robert | 21 | Mason | 23, Pitalpin Street, Lochee |

| 15 | Graham | David | 37 | Teacher | Stirling |

| 16 | Hamilton | John | 32 | Grocer | 16, North Ellen Street |

| 17 | Henderson | James | 22 | Labourer | 3, Church Street |

| 18 | Hendry | Elizabeth | 62 | n/a | Prior Road, Forfar |

| 19 | Jobson | David | 39 | Oil and colour merchant | 3, Airlie Place |

| 20 | Johnston | David | 24 | Railway Guard | Edinburgh |

| 21 | Johnston | George | 25 | Mechanic | n/a |

| 22 | Jack | William H | n/a | Grocer | 57, Mains Road |

| 23 | Kinnear | Margaret | 17 | Domestic Servant | 6, Shore Terrace |

| 24 | Leslie | James | 22 | Clerk | Baffin Street |

| 25 | Lawson | John | 25 | Plasterer | 39, Lilybank Road |

| 26 | McBeath | David | 44 | Railway Guard | 46, Castle Street |

| 27 | Macdonald | William | 41 | Sawmiller | 70, Blackness Road |

| 28 | Macdonald | David | 11 | Schoolboy | 70, Blackness Road |

| 29 | Mitchell | David | 37 | Engine Driver | 89, Peddie Street |

| 30 | Marshall | John | 24 | Stoker | 18, Hunter Street |

| 31 | Murray | Donald | 49 | Mail Guard | 13, South Ellen Street |

| 32 | Milne | Elizabeth | n/a | Dressmaker | n/a |

| 33 | Murdoch | James | 21 | Engineer | 1, Thistle Street |

| 34 | Millar | James | n/a | Flax Dresser | Dysart |

| 35 | McIntosh | George | 43 | Goods Guard | 25, Hawkhill |

| 36 | Neish | David | 37 | Teacher and Registrar | 51, Coupar Street, Lochee |

| 37 | Neish | Bella | 5 | daughter of above | 51, Coupar Street, Lochee |

| 38 | Ness | Walter | 24 | Saddler | 4, Bain Square, Wellgate |

| 39 | Ness | George | 21 | Engine Cleaner | Ogilvy Street, Tayport |

| 40 | Neilson | William | 31 | n/a | 53, Monk Street, Gateshead |

| 41 | Nicoll | Mrs Elizabeth | 24 | n/a | 46, Bell Street |

| 42 | Paton | James | 42 | Mechanic | Edinburgh |

| 43 | Peebles | William | 30-40 | n/a | n/a |

| 44 | Peebles | James | 15 | Apprentice Grocer | Newport |

| 45 | Robertson | William | 21 | Labourer | 100, Foundry Lane |

| 46 | Robertson | Alexander | 23 | Labourer | 100, Foundry Lane |

| 47 | Salmond | Peter | 43 | Blacksmith | 50, Princes Street |

| 48 | Scott | David | 26 | Goods Guard | 7, Yeaman Shore |

| 49 | Scott | John | 30 | Pipe Maker | n/a |

| 50 | Sharp | John | 35 | Joiner | 76, Commercial Street |

| 51 | Smart | Elizabeth | 22 | Domestic Servant | Union Mount, Perth Road |

| 52 | Spence | Annie | 21 | Weaver | 62, Kemback Street |

| 53 | Syme | David | 22 | Clerk | Royal Hotel, Nethergate |

| 54 | Taylor | George | 25 | Mason | 56, Union Street |

| 55 | Threlfell | William | 18 | Confectioner | 9, Union Street |

| 56 | Veitch | William | 18 | Cabinetmaker | 39, Church Street |

| 57 | Watson | David | n/a | Commission Agent | Newport |

| 58 | Watson | Robert | 34 | Moulder | 12, Lawrence Street |

| 59 | Watson | David | 9 | son of above | 12, Lawrence Street |

| 60 | Watson | Robert | 6 | brother of above | 12, Lawrence Street |

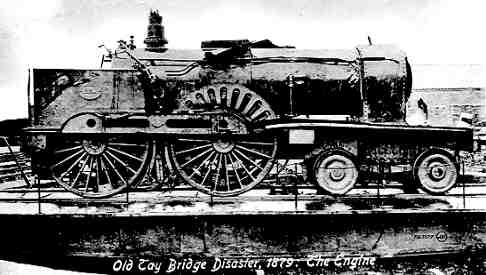

As you may remember, the title of this article is "A Single Survivor". Yet all on the bridge that fateful night were killed, So who was the "Single Survivor"?

Locomotive 224 .. the engine that carried the train to it`s watery grave, was raised .. refurbished and put back into service.

Indeed the small loco made several trips over the "NEW" tay rail bridge before being retired from service. Ironically the staff of the railway gave the small loco the nickname of "The Diver".

| © RIYAN Productions |